Review: The Fourth Part of the World

The Fourth Part of the World: The Race to the Ends of the Earth, and the Epic Story of the Map That Gave America Its Name

by Toby Lester

Free Press, 2009. Hardcover, 480 pp. ISBN 978-1-4165-3531-7

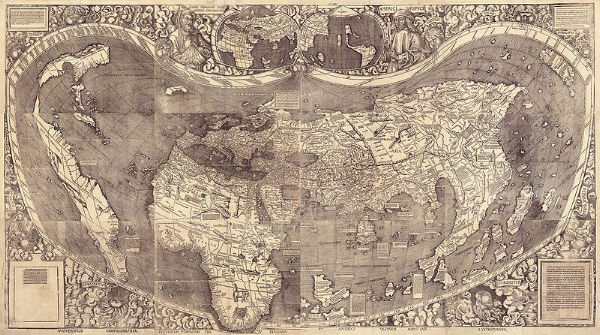

We’ve heard a lot about Martin Waldseemüller’s map in recent years. Printed in 1507, it was the first map to give the name “America” to the New World. One thousand copies of the large, 12-section map were produced; only one copy is known to exist today — and that one was only rediscovered in 1901 by Father Joseph Fischer (who would later gain some posthumous notoriety as the prime suspect in the Vinland Map controversy). A century later, the Library of Congress bought the map for $10 million; it has been on display, in an argon-filled case, since 2007.

We’ve heard a lot about Martin Waldseemüller’s map in recent years. Printed in 1507, it was the first map to give the name “America” to the New World. One thousand copies of the large, 12-section map were produced; only one copy is known to exist today — and that one was only rediscovered in 1901 by Father Joseph Fischer (who would later gain some posthumous notoriety as the prime suspect in the Vinland Map controversy). A century later, the Library of Congress bought the map for $10 million; it has been on display, in an argon-filled case, since 2007.

It was that record-breaking purchase by the Library of Congress that piqued Toby Lester’s interest in the subject; a few years later, the result is his first book, The Fourth Part of the World: The Race to the Ends of the Earth, and the Epic Story of the Map That Gave America Its Name.

What’s initially surprising about The Fourth Part of the World is how little time it spends on Waldseemüller, his collaborator Matthias Ringmann (who coined the name “America” for the map Waldseemüller drew), and the map, globe gores and book (the Cosmographiæ Introductio) that they produced in 1507. Maybe a fifth of the book deals with the map and its creators. Lester has not produced a popular history of the famous map in isolation; instead, he’s produced an ambitious book that places Waldseemüller’s creation in its cultural context — and has managed to do so in a manner that is highly readable, entertaining and gripping.

“Before long I realized that the map offers a window on something far vaster, stranger, and more interesting than just the story of how America got its name,” Lester writes in the preface.

It provides a novel way of understanding how, over the course of several centuries, Europeans gradually shook off long-held ideas about the world, rapidly expanded their geographical and intellectual horizons, and eventually — in a collective enterprise that culminated in the making of the map — managed to arrive at a new understanding of the world as a whole.

This book tells the story of the Waldseemüller map in two distinct ways: as microhistory that focuses on the little-known and fascinating story of the making of the map itself, in the years leading up to 1507; and as a macrohistory that traces the convergence of ideas, discoveries, and social forces that together made the map possible — a series of overlapping voyages, some geographical and some intellectual, some famous and some forgotten, that made it possible to depict the world as we know it today. (x-xi)

So, after a prologue that recounts how the last surviving known copy of the map was rediscovered, we jump back to an English monastery circa 1255 — more than 250 years before the map’s publication. Lester starts us here, with T-O maps representing the known world, with Asia on top, Europe on the left, Africa on the right, and Jerusalem in the centre. (America was, therefore, the “fourth part of the world,” whence the title.) Europe had a long way to go from such representations of the world before they could arrive at a map like Martin Waldseemüller’s. It would require the reports from several journeys to Asia, the rediscovery of Ptolemy’s Geography, which provided latitude and longitude for a number of locations that could reconstitute a map of the classical world, and an increasing number of voyages, both westward and around Africa, that both revised and expanded the European understanding of the world. Marco Polo, Roger Bacon and Columbus all make their appearances, as does Amerigo Vespucci, whose letters, almost certainly fakes, ignited the European imagination and led Ringmann to propose his name for the New World.

Waldseemüller’s map, we learn, is a hybrid of all of these sources: the known world greatly resembles the maps reconstructed from Ptolemy, to which were added rather conjectural maps of Asia, the Portuguese voyages around Africa, and the discoveries in the New World. It was quickly superceded by newer, more accurate maps (which is precisely why it all but disappeared); interestingly, it was even superceded by Waldseemüller himself: the name “America” disappeared from his later maps. Even so, the map made enough of an impression that, Lester argued, it influenced Copernicus’s cosmological thinking.

What I found truly fascinating is how the European imagination managed to blend what was believed to be true about faraway lands — the myth of Prester John simply refused to disappear, to the confusion of the peoples encountered by Europeans who kept assuming they were he — with what was held to be true because it came from antiquity and with what was directly observed. Of this, Waldseemüller’s map was a prime example. It’s also a vivid look at how Europeans understood the world around them — and it wasn’t the same way we see it today.

For me, the reminder that maps have their context is also extremely useful when dealing with some of the map hoaxes and forgeries out there. Even though the physical map all but disappeared for centuries until that last copy was rediscovered, the map was known to have existed. It was referred to. It was discussed. (If nothing else, there was the Cosmographiæ introductio.) It did not, in other words, exist in a vacuum. Compare that with the Vinland Map or Liu Gang’s purported 1418 map, both of which exist wholly isolated from the rest of the accepted historical record, and you note the significance of that. (Not that that’s what Toby Lester had in mind with this book, but it’s what occurred to me when I read it.)

For its big-picture look at the Waldseemüller map within its cultural, religious and intellectual surroundings, this book is definitely worth reading.

Previously on Toby Lester’s Fourth Part of the World: The New York Times on Two Map Books; Updates on Two New Books; The Fourth Part of the World.

Previously on Waldseemüller’s map: Waldseemüller Symposium at LOC in May; The Washington Post on Waldseemüller; Which Waldseemüller?; Waldseemüller Map Exhibit Opens Thursday; Upcoming Books on Waldseemüller; More About Waldseemüller; Waldseemüller Map Formally Transferred; Waldseemüller Map Stamp Issued; Encasing Waldseemüller’s Map; Waldseemüller’s Map Goes for £545,600; Auction of First Map of the New World.

- Buy The Fourth Part of the World at Amazon.com

Comments

blog comments powered by Disqus